Restorative Dentistry and Periodontics

Introduction

One of the most prevalent infectious diseases in humans is periodontal disease. It is the result of a complex relationship between microflora and non-bacterial factors, specifically, host and environmental factors. The etiology of gingivo-periodontal conditions is multi-factorial. These multiple factors are grouped into three categories:

1. Microbial factors.

2. Host response.

3. Environment.

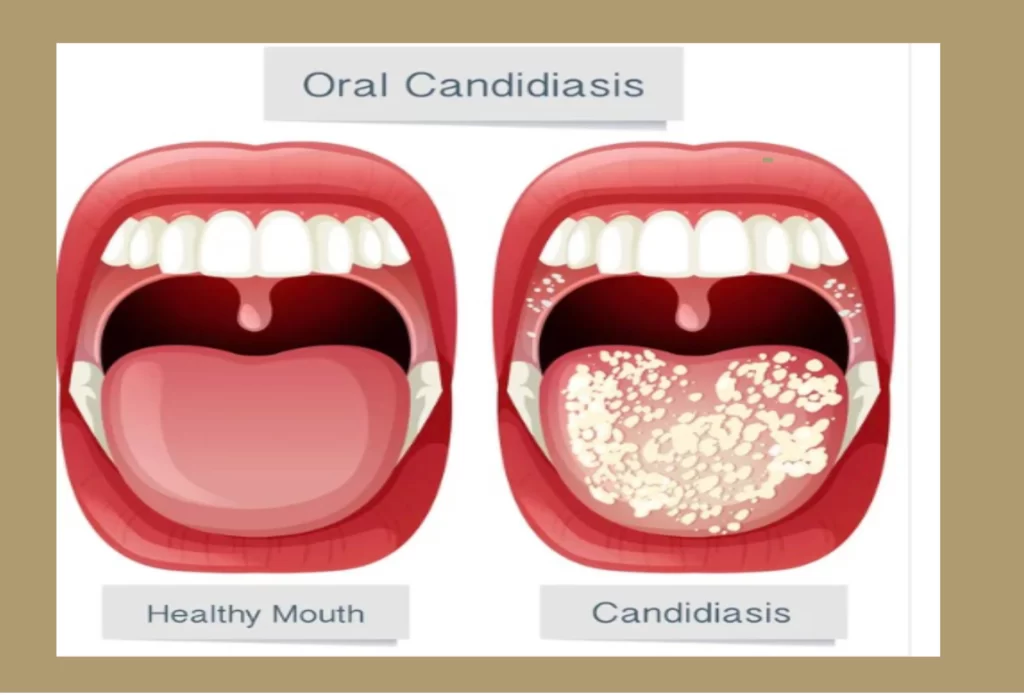

Microorganisms found in the oral cavity can be modified by local or general factors.

Local factors include poor oral hygiene, improper dental restorations (mismatch of margins, restoration contours, proximal relationship, surface smoothness, etc.), food packaging, and inadequate orthodontics capable of retaining plaque.

The general environmental factors are tobacco use in its various forms, psychic factors such as stress, and socioeconomic factors.

There is an intimate interrelationship between restorative dentistry and periodontal tissues.

For periodontal health to exist, periodontal health must be conceived, constructed, and installed with periodontal criteria. This means that restorative dentistry will be subordinated to the periodontal tissues and not these to it, and it will be periodontics rather than prosthetics and dental surgery that will guide us better for the replacement of missing teeth. In this way, a correctly designed and constructed prosthesis, in perfect harmony with the function of healthy tissues, will maintain lasting gingival and period-dental health and this mechanical resource will remain in the mouth for a long time without damage.

But when it is designed, built, or installed without taking into account the tissue response, it will initiate, in a healthy mouth, the claudication of the tissues that support the teeth and will aggravate those already affected by the periodontal lesion, making any repair and recovery impossible. Hence, restorative dentistry is considered an important risk factor in the etiology of periodontal disease.

It is true that operative procedures (carving, impression, cementing, etc.), when not handled with care, involve damage to the gingival tissues, which are traumatized and injured.

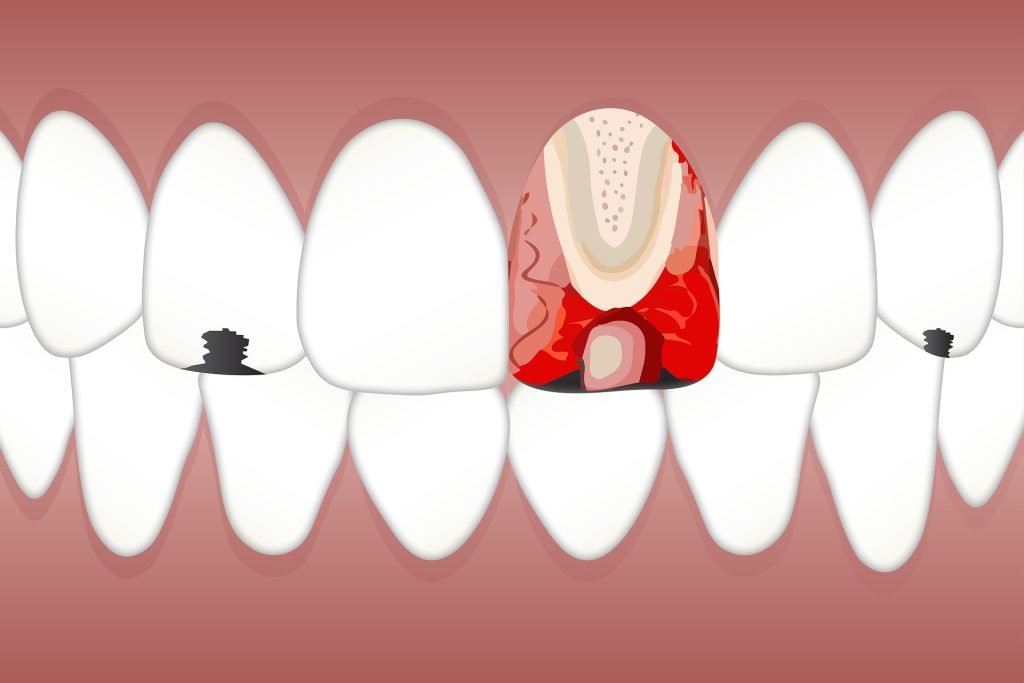

From a biological point of view, this trauma has no major repercussions due to the repair capacity of the gingival tissue, which allows it to heal in a short time. However, in spite of this repair, if the margin of the crown is mismatched, irregular, or unpolished, and there is a certain thickness of cementum between the crown and tooth due to this mismatch, the gingiva will be continuously affected by the accumulation of bacterial plaque, which will be manifested from the clinical point of view by inflammation.

With very precise and refined laboratory techniques, optimal crowns can be achieved in terms of their location, termination, and gingival adaptation. This result is not obtained regularly, but only under ideal conditions and for experimental purposes, because it is not achieved as a practical purpose for the thousands of crowns that are installed daily in the world; this is due to the fact that, disregarding the professional skill so important for the final success, the resources provided by modern laboratory techniques are not only not interpreted but are not performed correctly, for the production of a relatively optimal crown.

Oral health care is the guarantee for a healthy, complete, and beautiful set of teeth for life. In addition, people want to retain their chewing function forever and are not resigned to the progressive loss of teeth as an inevitable consequence of aging.

Almost everyone in developed and developing societies wants to have a normal dentition, not only for functional reasons, but also because it means better psychological well-being, better self-image, and, consequently, social success.

There is a widespread demand for the general dentist to integrate periodontal therapy and prosthodontics. This is due in part to the increasing number of adult patients with periodontal pathology and the broad criterion of preserving the natural or restorative dentition in good health, function, and esthetics. This goal can best be achieved with teamwork that includes the periodontist, general practitioner, and prosthodontist, and can be expanded to involve the endodontist, orthodontist, and oral surgeon.

We believe that the topic chosen can be very useful, since the problem addressed is very frequently encountered in daily clinical practice, for restorative or purely esthetic reasons. Its purpose is to teach the different situations in which restorative dentistry can act as a risk factor, favoring the retention of bacterial plaque, in the etiology of gingivo-periodontal disease.

gingivo-periodontal disease. Simultaneously with the observation of the errors that arise in daily practice, the ideal working conditions will be established.

This article is intended to be a guide so that the general practitioner can perform restorative dentistry as close to the ideal as possible, without causing periodontal lesions and preserving the health of the gingival and periodontal tissues in the long term. The aim is to enable the reader to transfer the knowledge presented in this article to daily practice.

The original idea for this article was born from conversations with general practitioners and arose from the need to fill a gap in restorative dentistry and periodontics, which today the experience of more than twenty-five years of teaching advanced and specialization courses, together with extensive private practice, makes it possible to cover.

This series of articles is designed for the dentist who wishes to recognize errors and concepts in his daily work.

Techniques detailed in this article have wide application, both in the periodontally healthy patient and in the patient suffering from periodontitis, whether mild or severe.

The article focuses on the most common problems seen in everyday practice and when in each clinical case a realistic solution is sought in accordance with the patient’s limitations

The constant evolution of dental techniques and products brought about by scientific research makes information rapidly obsolete. Thus, although the classic textbooks provide indispensable knowledge for basic professional training, any good observer can see that it is becoming increasingly difficult for the general dentist to keep up to date; it is also clear that students must have a guidebook to interest them in a philosophy based on prevention.

Responses